Phylloxera came, saw, and a little over a hundred years ago destroyed one of Balaton’s most prominent products: wine. The disaster led to the extinction of several valuable grape varieties, and drove many winemakers to an early grave or out of the region. Those who stayed behind started fighting the ruthless infestation with carbon disulfide and flooding, eventually resorting to reinventing winemaking on the less traditional, sandy terrain of the south shore.

The history of viticulture and vinification on the Balaton Uplands is very much based on the winemaking traditions of the Romans. From the time they started working the land here, the region was a prolific wine grape growing area for hundreds of years thanks to its advantageous geographic and climatic properties. By the 1800s, however, Hungarian wines could no longer compete with the products coming from Western Europe, and later the United States due to unprofessional treatment practices, difficulties with bottling, and the old-fashioned state of Hungarian wine trading. From the middle of the century, wines were imported in bulk from the United States of America to the countries of Europe, including Hungary. New, more resilient grapevines were also brought in, which were capable of thriving in colder climates, and were immune to the harmful effects of powdery mildew. The sturdier species had a downside as well: it introduced a completely unknown pest named phylloxera to the continent.

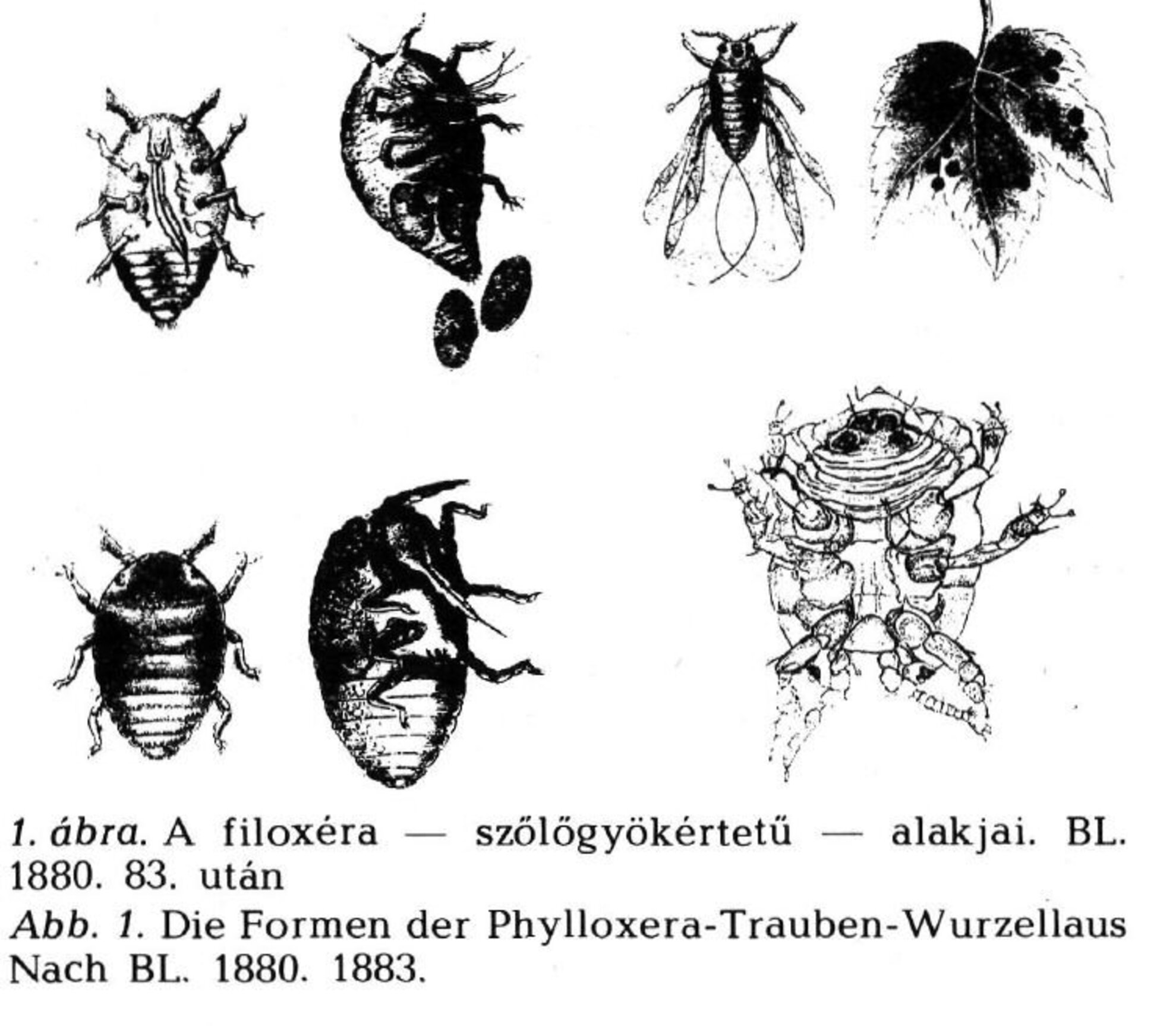

What is phylloxera?

Grape phylloxera had already been identified in America by the mid-19th century as a tiny, sap-sucking, yellowy green insect that feeds on the roots and fresh shoots of grapevines. When a plant is infected, lumps of various sizes form on the roots, the leaves go yellow, and the grapes dry out gradually. As the infection progresses, the roots continue to deteriorate until they die completely.

Hard ground, which was found in abundance in Hungary at the time, was one of the main prerequisites of a mass infection. Disaster struck on the continent in 1865 with French winemaking being the first to be affected, and the "plague" eventually moved on to the Carpathian Basin in 1875 via southern Europe.

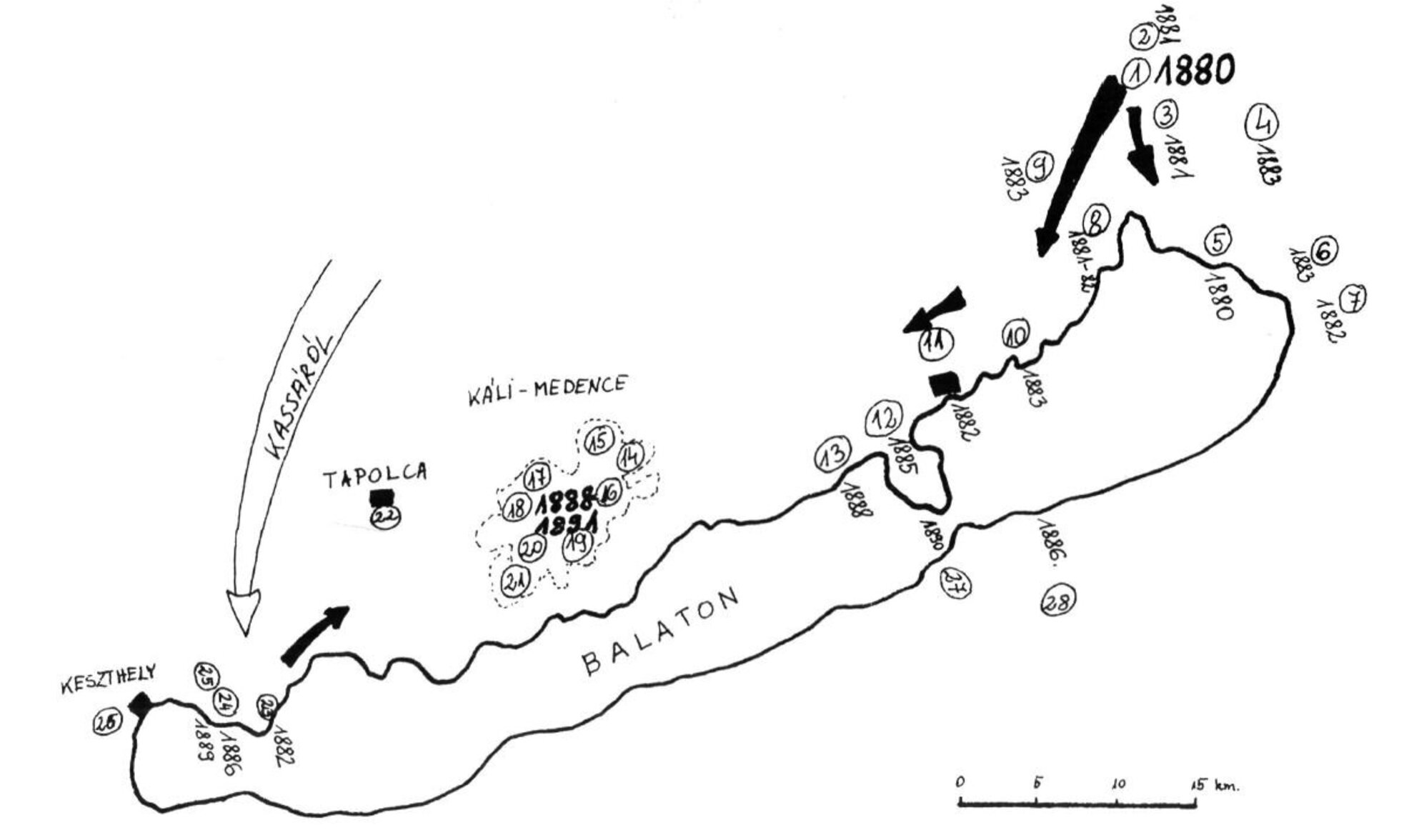

The first instance of phylloxera infestation around Balaton was recorded in 1878 in Balatonfőkajár. The vineyards of Balatonkenese – making up the biggest grape growing area of the region with a total of more than 500 hectares – were completely wiped out by the insects between 1880 and 1885. The Káli Basin was attacked on two fronts: from the direction of Veszprém and Balatongyörök. By 1889, the phylloxera epidemic had reached the vicinity of Balatonfüred, and it arrived in Szántód, on the south shore a year later, in 1890. Some of the bigger estates on the north shore were able to salvage a portion of their vast vineyards, but the sandy parts of the South Balaton area – like Balatonkeresztúr and Balatonboglár, which had never been known for large-scale wine production – were entirely planted with the new varieties. Devastation on the Balaton shore was massive: about half of the vineyards were obliterated in Veszprém County, while Zala County saw the destruction of two-thirds of its growing regions.

Grapevines love carbon disulfide and water

After years of experimentation, France finally came up with two different solutions to the pressing problem: one of them, a carbon disulfide gas treatment involved injecting a foul smelling, transparent, volatile substance into the ground on four points of a 15-centimeter radius around the roots, which was an effective way of killing a significant number of the insects. Apart from being very expensive, this method also required a lot of equipment, which was the main reason why it spread so slowly in Hungary. Flooding was the other weapon devised against phylloxera: it was discovered that the insects died when the vine rows stood in 20-25-centimeter deep water for several weeks. The only disadvantage of this technique was that it only worked in relatively flat areas.

Growing grapes in sandy soil became a big success all over the country because it prevented the insects from digging a secure route from one plant to the other. As the American grape varieties were expensive to grow and yielded poor quality wine, winemakers around Balaton much preferred planting the grapevines in the sand.

Suicide or migration

Before the phylloxera epidemic hit Europe, Badacsony’s famous grape variety called “Ürmös” had been as renowned as the aszú wines of the Tokaj region. Also known for its Kéknyelű and Somszőlő, Badacsony was the first around Balaton to be pronounced a wine region in its own right in 1896. Statistical data compiled by economist and statistician Károly Keleti in 1873 suggests that 76 different wine grapes were cultivated in Hungary before the appearance of the phylloxera infestation. With all the sub-varieties, we could be talking about hundreds of grapes, most of which are unknown today.

Even though wine production was relaunched after the turn of the century, several older varieties traditionally grown at Balaton – such as Somogyi white and Juhfark – were either entirely eliminated or pushed to the side as a result of the phylloxera outbreak. In his 1902 book titled “The ethnography of the Balaton area’s population”, János Jankó makes mention of about 60 local grape varieties. Jankó notes that Kéknyelű “is being cut down in an intensive manner, as it yields delicious wines, but only in very small amounts”. Winemaking after the phylloxera incident was dominated by the then newly planted grapes that are still available today, among them Welschriesling, Pinot gris, Ezerjó, Chardonnay, and Szilváni.

The extent of the destruction is hard to describe with numbers, but local families were all of a sudden faced with the loss of their livelihood. In one of the national journals of the profession, winemaker József Keőd said that in his village alone four people committed suicide in their own wine cellars in 1890. “Three of them were strong, hard-working family men, and the fact that they took their own lives in their cellars highlights the reason of their desperation in a very poignant way.” While most people tried to find a solution to the problem, many decided to move away in search of new opportunities. Some of them went only as far as the Great Plains of Hungary, but others traveled all the way to Slavonia, Croatia, and even America. Unemployed farm hands were hardest hit by the disaster, which prompted them to leave in huge numbers.

Did you know which Mary is the namesake of Balatonmáriafürdő?

The state was eager to support and subsidize the adoption of the new plants and methods, as well as the cultivation of the phylloxera-resistant grape varieties grown in sandy soil. The farmers that were ruined by the phylloxera invasion were offered agricultural loans with favorable conditions - such as tax exemption after planting - to be able to rebuild their destroyed vineyards, but the scheme was not hugely popular due to the high costs involved and the slow return on the investment. Even with these rescue routes available, many local vineyard owners were forced to sell everything they had at auction.

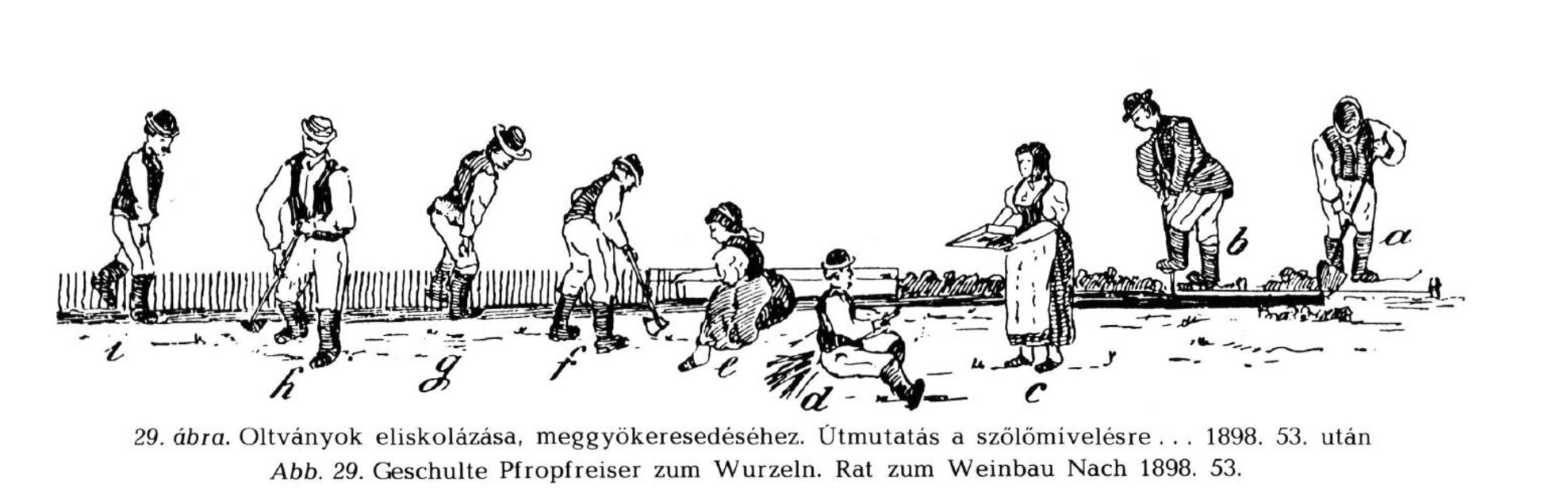

The government tried to help in other ways, too: graft gardens and vineyardist schools were set up, and technical literature was widely circulated among affected farmers. By Word War I, the total area of Balaton vineyards exceeded 400,000 hectares.

Count Imre Széchenyi, the government commissioner responsible for boosting winemaking on the south shore oversaw the planting process carried out in the sandy areas, among them in Balatonkeresztúr. Ironically, the demise of the traditional growing regions in the north had an immensely positive effect on winemaking on the south coast. The government wanted to establish the new vineyards as close as possible to the ones that had been destroyed to stop small-scale farmers and agricultural laborers from leaving: those previously based on the north shore were given the chance to rent grape growing plots south of the lake.