A nearly century-old building thick with science has innumerable great (not necessarily biology -related) stories to tell. The doorknob of the Limnological Institute in Tihany was in the hands of people, like the one-time Minister of Culture and reformer of education Kuno von Klebelsberg, former Prime Minister István Bethlen and the physiologist known for discovering Vitamin C, Albert Szent-Györgyi; then there was the case of the disappearance of a Vaszary painting of inestimable value; a little boy peeing in the wrong place led to a scientific breakthrough; and they are responsible for checking the water quality of Lake Balaton.

So what on earth is limnology? We'll save you the trouble of googling: it is the study of inland waters. About a 100 years ago, this was one of the most significant branches of biological research. The reason is simple: from the beginning of the 20th century until the end of World War II, animal testing and experiments were conducted on fish instead of mice and rabbits. This is why the Limnological Institute in Tihany and several other European institutes of the period were established. The majority of people considered this branch of science useless back then, being of the opinion that PM István Bethlen could have spent the funds on something more useful in Hungary stricken by war. The locals were so averse to the idea that they dubbed the institute "water beetle shoer."

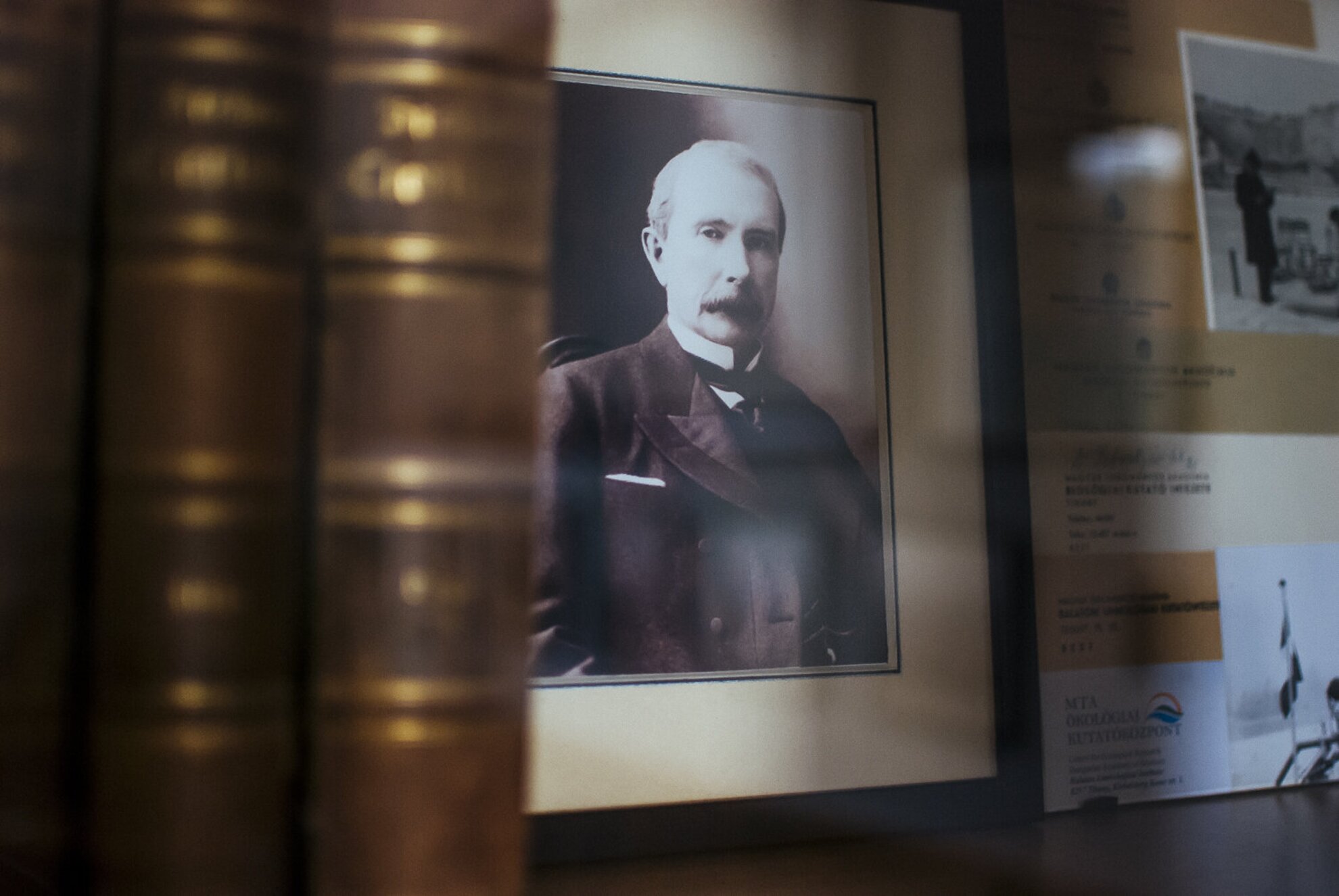

At the laying of the foundation stone, Minister of Education Kuno von Klebelsberg stated, 'I claim it would indeed be great squandering to do what we do in a small-time manner due to petty pusillanimity.'

Lake Balaton introduced to Europe

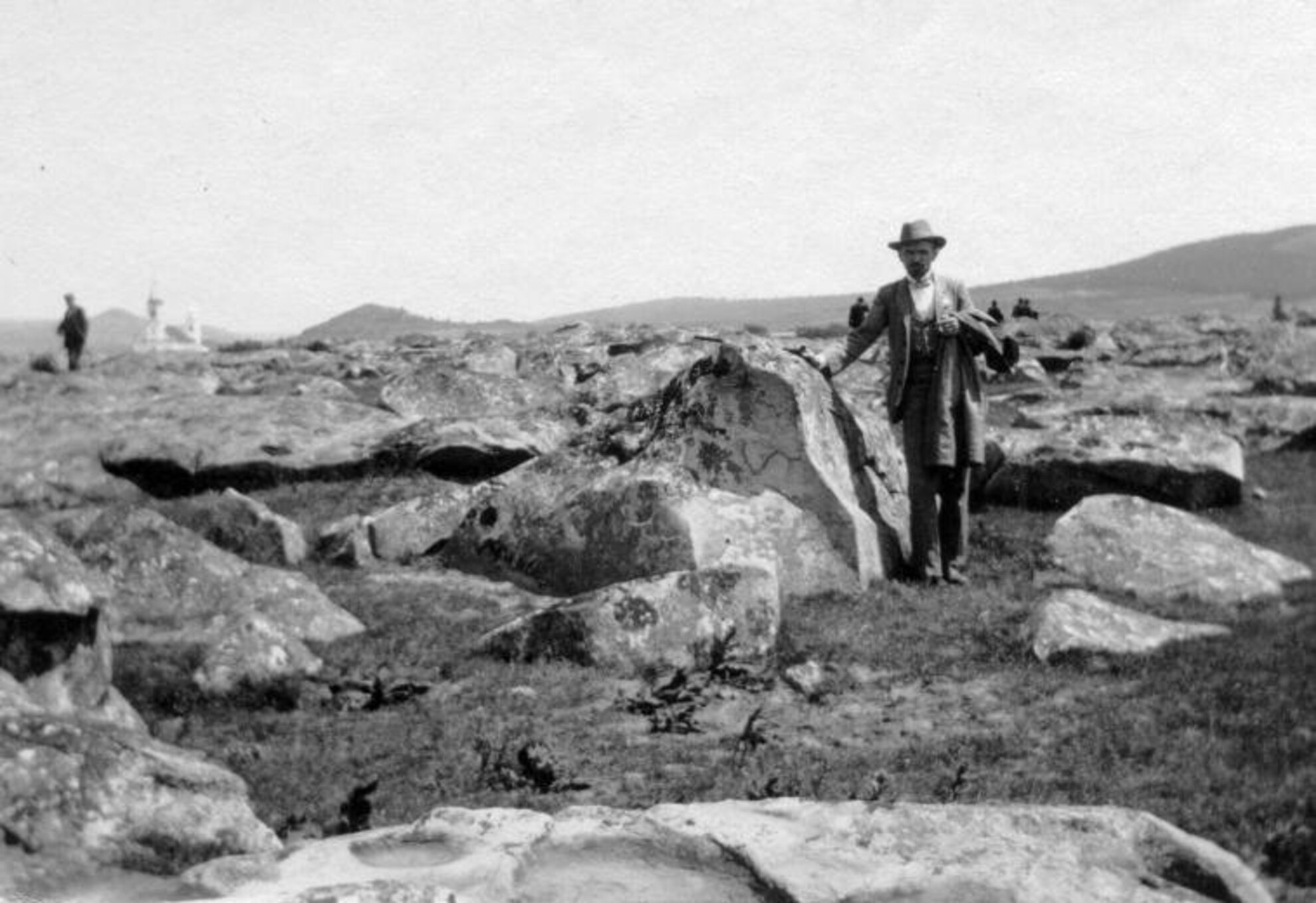

The scientific assessment of Lake Balaton began after the Ottoman occupation of Hungary. The first (military) maps of the area were drawn up in the first part of the 8th century and in the second part of the 19th century.

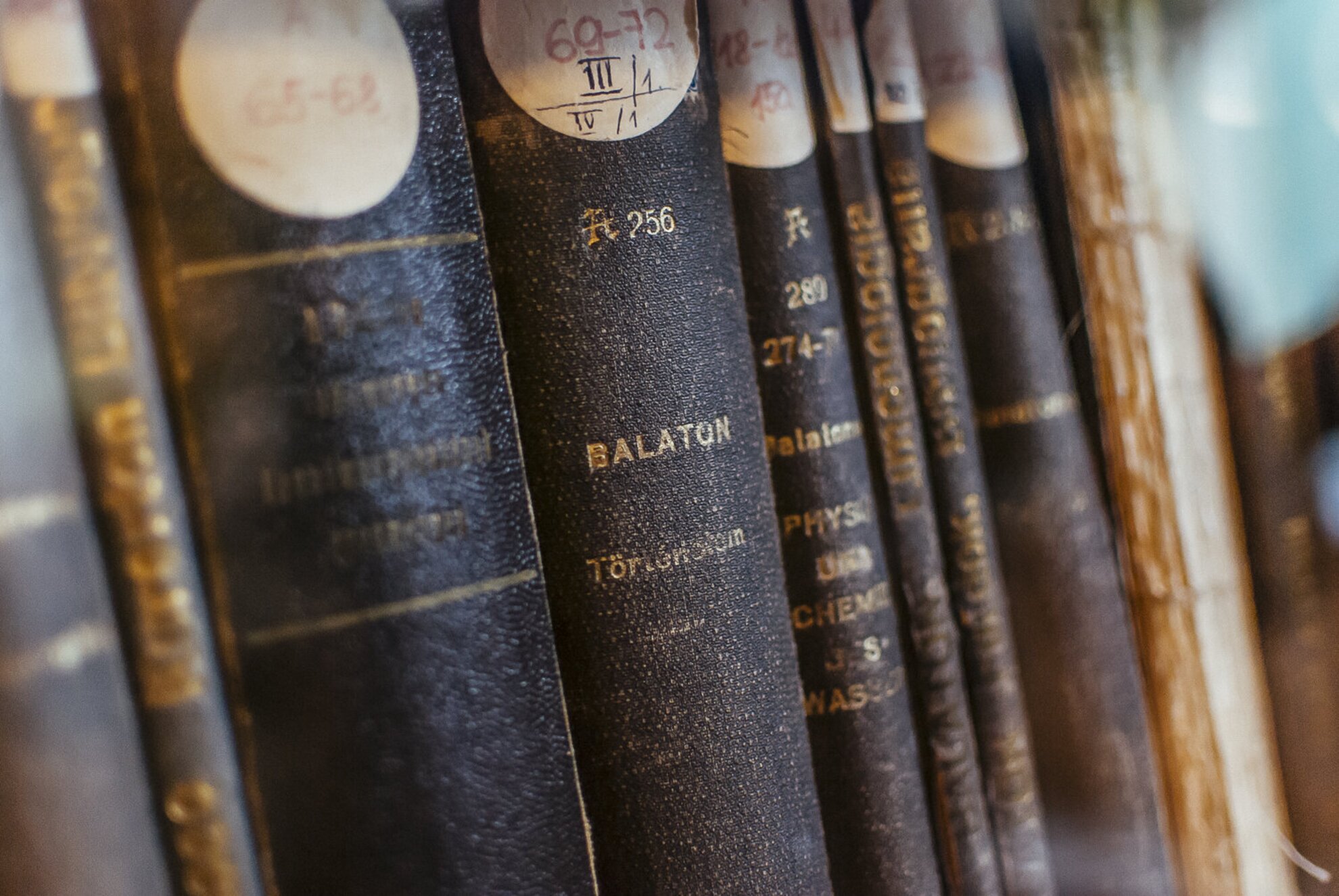

The in-depth study of the flora and fauna of the Lake was initiated by the Balaton Committee of the Hungarian Geographical Society in 1891. In the course of the following 29 years, natural scientists elaborated on the detailed description of the geological history, and the physical, chemical and biological characteristics of the Lake. It took a 32-volume series edited by Lajos Lóczy to accommodate their innumerable findings. The Results of the Scientific Study of Lake Balaton were also published in German, so the Lake made its way to the international scientific scene.

Kuno von Klebelsberg believed that the national consciousness broken by the Trianon Treaty could benefit from an independent research institute that provides an opportunity to hundreds of internationally recognized scientists to excel. The culture politics of the Minister of Education fit perfectly into the economic boosting program of PM Bethlen. Klebelsberg was convinced by a respected researcher, '..most of the water organisms are transparent; with adequate magnification and lighting we can see the whole living body, we see not only the physical appearance but also all the organs, the pulsing heart, the single blood cells ejected from it, the stomach’s functions, the bowel movements and the other life functions which in more complex bodies can only be demonstrated after dissection. However, water organisms are extremely fragile and can easily die. Therefore to study them the opportunity should be given on the spot by the establishment of a research institute set up by the water.'

How the most modern institute of Europe turned out

In 1927, a year after the laying of the foundations stone the construction of the institute with its state-of-the-art laboratories, elegant restaurant, panoramic aquariums and guest rooms was completed. The building fit well into the concept of the new Tihany bathing resort, which was also realised in a few years, with the exception of the spa hotel.

The building of the Limnological Institute (then: Hungarian Biological Research Institute) was designed by István Kotsis, who had impressed von Kelbelsberg with one of his earlier works, the palace of Archduke Joseph August of Austria. The complex has three parts: the central laboratory building is flanked by the accommodation of researchers on one side and that of the permanent staff on the other.

The laboratories' aquariums held water pumped from Lake Balaton and sea water from the Adriatic Sea, transported via the Danube and the Sió Channel. The institute used to have a private beach, a boat named after von Klebelsberg and a boat house.

The Hungarian state commissioned János Vaszary to paint a huge canvas displaying a stylized version of the flora and fauna of Lake Balaton as seen through a veil of water, to be placed in the upstairs course room. According to István Kotsis, the scientists working in the institute disliked the painting, for they were constantly occupied by 'determining the names of stylized animals and plants.' Future Communist years solved that problem. The canvas was transported to the Hungarian Academy of Sciences in Budapest at the end of the 1950ies, but the only state-commissioned work by Vaszary mysteriously disappeared somewhere on the road. 'A mélység világa' (The World of the Deep') has never been recovered.

The institute started operation with a physiology and a Balaton research department. A buzzing intellectual life soon established itself here with future Nobel laureate scientists working, like Otto Loewi, Paul Weiss or Albert Szent-Györgyi. During WW2, the head of the institute managed to put the building under the protection of the International Red Cross, so it survived the war almost unscathed; the number of scientists, however, significantly dropped in those years: many took teaching jobs in Cluj Napoca, while others were enlisted in the army.

The 'Manneken Pis' and the artificial carps

Some of the persistent research efforts received a push from luck as well. In the 1950ies, several experts were working on the possibilities of the artificial propagation of carps. Neither of them imagined that they would have to thank the technique and the accompanying world-fame to a peeing child. Fish biologist Elek Woynárovich, the head of the institute at the time was experimenting with fusing the gametes in a bowl for long time, but the eggs somehow always stuck together before fertilization.

On one occasion, he arrived to the institute with his kids. Busy with work, he did not have time to take his son to the loo, so he gave him one of the fish egg bowls to pee in. To his great surprise, he accidentally discovered the missing link: the compound called urea, also found in humane urine, did finally separate the eggs.

This gave the green light to mass industrial carp propagation. Soon after, Elek Woynárovich left to teach artificial fish breeding methods to experts in protein-poor countries. He travelled to Nepal, Venezuela, Madagascar and Brazil as well. His is only one of the many stories that began at the Institute and reached world-fame.

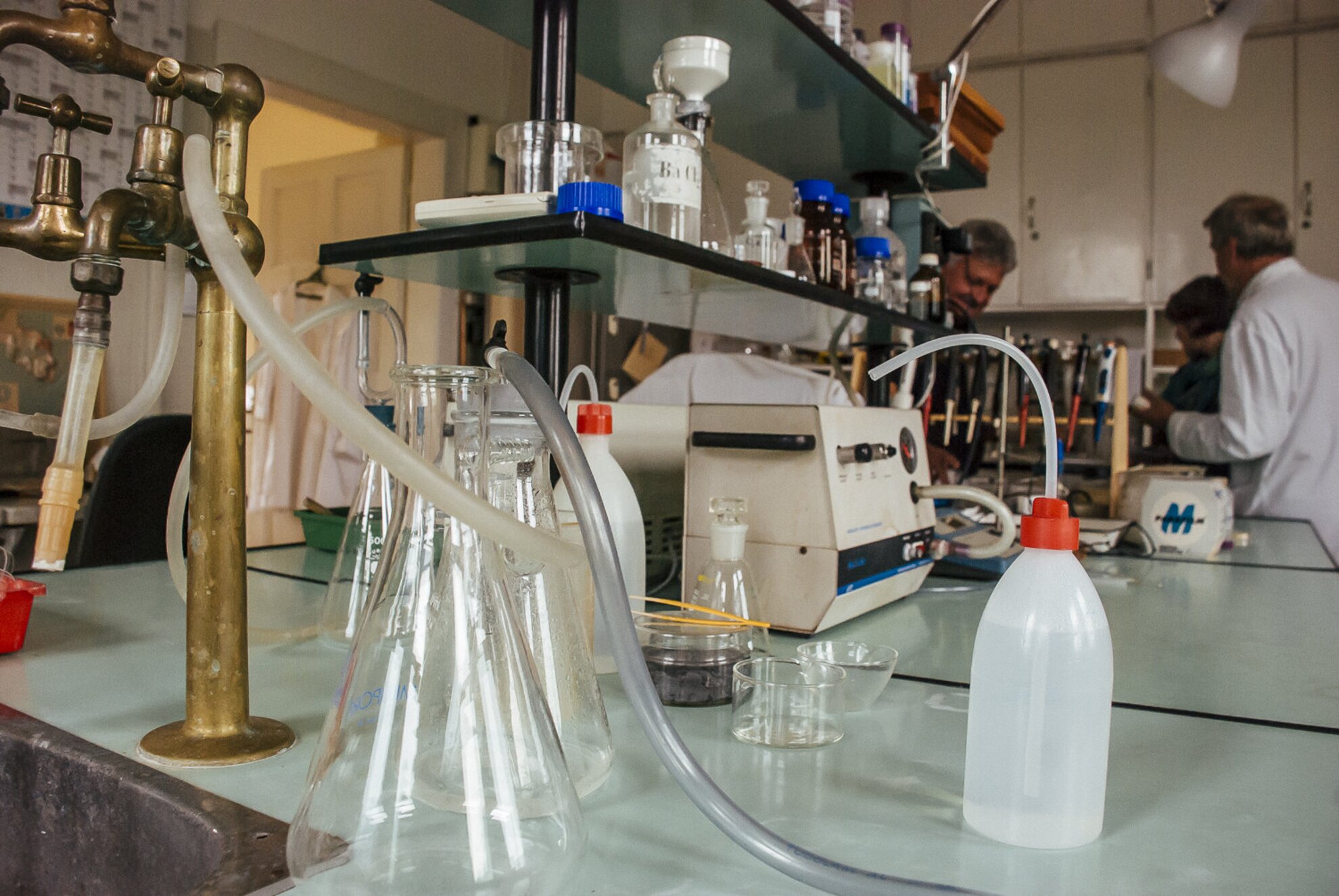

The institute today

Balaton research was delivered again into the centre of attention in 1965 and 1975 due to mass fish deaths and decreasing water quality. From the 1970ies, state-coordinated campaigns were launched one after the other in order to save Lake Balaton. The institute's focus was turned back to hydrobiology, and the Hungarian Academy of Science re-christened it to Balaton Limnological Institute in 1982. Researches have been continuous since.