The need for the institutionalized development of the Balaton region first emerged at the beginning of the 1950s: the National Planning Office devised a data collection scheme and commissioned a number of preliminary examinations to be carried out. Following the uprising of 1956, the central authority wanted to depoliticize the masses by making relative well-being, including holidays at Lake Balaton, available to everyone. But in order to accommodate the host of holidaymakers, infrastructural developments were needed in pretty much every field of life, such as roads, railway corrections, new motorways, marinas, beaches, lodgings, catering establishments and more.

A uniform image

By the end of the 1950s, the project leaders had realised that the development of Balaton requires a unified plan and a region-conscious attitude. In 1957 the Ministry of Construction commissioned the first regional plan of Balaton, and created the position of chief architect of Balaton, both of which had been without precedent until then. The Balaton Management Committee (BIB) was set up in the same year. The institutional foundation necessary for the development of the region was complete, and the funds were provided in the form of annual plan-based credit.

The plan called for the comprehensive examination (below and above ground) of the area surrounding Lake Balaton in terms of geological characteristics, settlement patterns, forests and vineyards, and the planning process soon zoomed in on individual buildings. The regional plan contained provisions for the public utilities system and the use of local lands, also taking into consideration the future role of Balaton settlements.

The function of each settlement played a determining role in the planning phase, with existing properties and future demands playing into the equation. For example, the position of the beach was chosen based on whether the settlement was a preferred destination for one-day trips or longer vacations.

By 1958, both the settlement plan and the final construction drawings had been finished, and construction began on the first sites despite the fact that the government’s seal of approval for the project came only five years later. The primary task was to set up the basic establishments for each area: public utilities, sidewalks, parks, beach infrastructure, food stands, shops, restaurants and seasonal lodgings were created around the same time. The plan received the prestigious Abercrombie Award at the 1965 world congress of the International Union of Architects.

Company motorbike and unlimited train travel

Chief Architect Tibor Farkas laid down the plan with his team of chief engineers, István Bérczes, who was responsible for the north shore, and Károly Polónyi, who was tasked with development on the south side. After the plan was complete, the trio went through the building permits of around 40 settlements (averaging about 100 per week). Most plans – except for those pertaining to public institutions – were executed by local craftspeople, who often employed poor and unrefined solutions.

Due to the large number of construction projects, there was no time for the in-depth examination of the plans – strategically positioned areas were prioritised over other sites. The worst plans were redesigned by the chief architects of BIB. Consultation days were held on both the north and the south shore to give property developers an opportunity to obtain advice.

The memoir of south shore chief engineer Polónyi reveals that he had a three-year commission, during which he had access to a company motorbike as well as an unlimited pass valid on all MÁV routes. From early spring through November, he slept under a tent pitched on a Star keelboat in the yacht club of Balatonföldvár. In exchange, he took on the roles of client, authority and architect: he was responsible for everything from regional planning to personally overseeing the planning process. The following lines bear testimony to the great work they achieved:

“By submitting the Balaton Regional Draft Plan, we managed to dissuade the government from creating a holiday resort similar to the Romanian resorts by the Black Sea and the Bulgarian Gold Coast, where tourists from the west can spend their foreign currency in an area separated from the local community. Instead, we set out to reform the region as a whole, as a living organism with carefully selected investments. Our main aim was to create infrastructural investments that everyone could benefit from, including locals, holidaymakers, tourists, Hungarians and foreigners.”

Polónyi had several other outstanding professional achievements as well, all of which were in line with the high standards of the international, late modern trends in architecture. Built in 1960 and comprising 20 double rooms with bathroom, the motel of Tihany was erected in accordance with Polónyi’s plans. Hot water was available in only two bathrooms, while the water circulating in the black pipe above the roof was heated with the help of the sun.

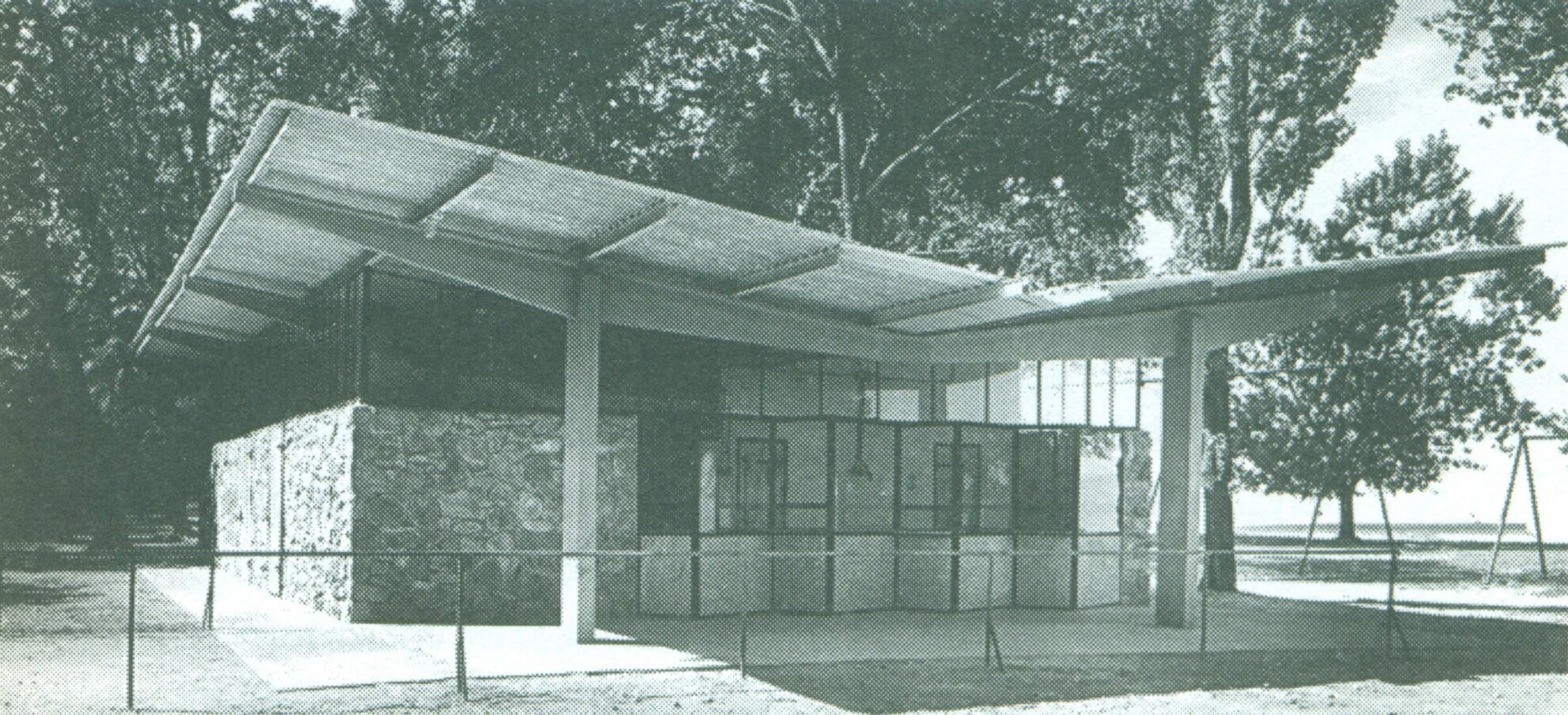

Polónyi also designed some simple, yet excellent seasonal buildings, which were easy to assemble, take apart and transport. As these were used only in summer, all they needed was a corrugated sheet roof slanted at the right angle to provide a constant draft with the help of the temperature difference between the sunny and shaded side. The outer walls were made from local fieldstone, and the inner walls from brick, planks or sometimes painted fishing nets. Over a period of two years, 28 such buildings were constructed to fulfil a wide variety of functions. Most of them were erected at the beach as entrance booths, changing cabins and food stands, and some of the other buildings were light steel structures used in similar ways.

Simple and simplistic

As the structural plans could be obtained by anyone for a small fee, similar buildings executed in ever-poorer quality soon cropped up all over Balaton and the whole country. Transformed to the point of being impossible to recognize based on the original plans, these structures were trying the patience of beauty-loving people for decades.

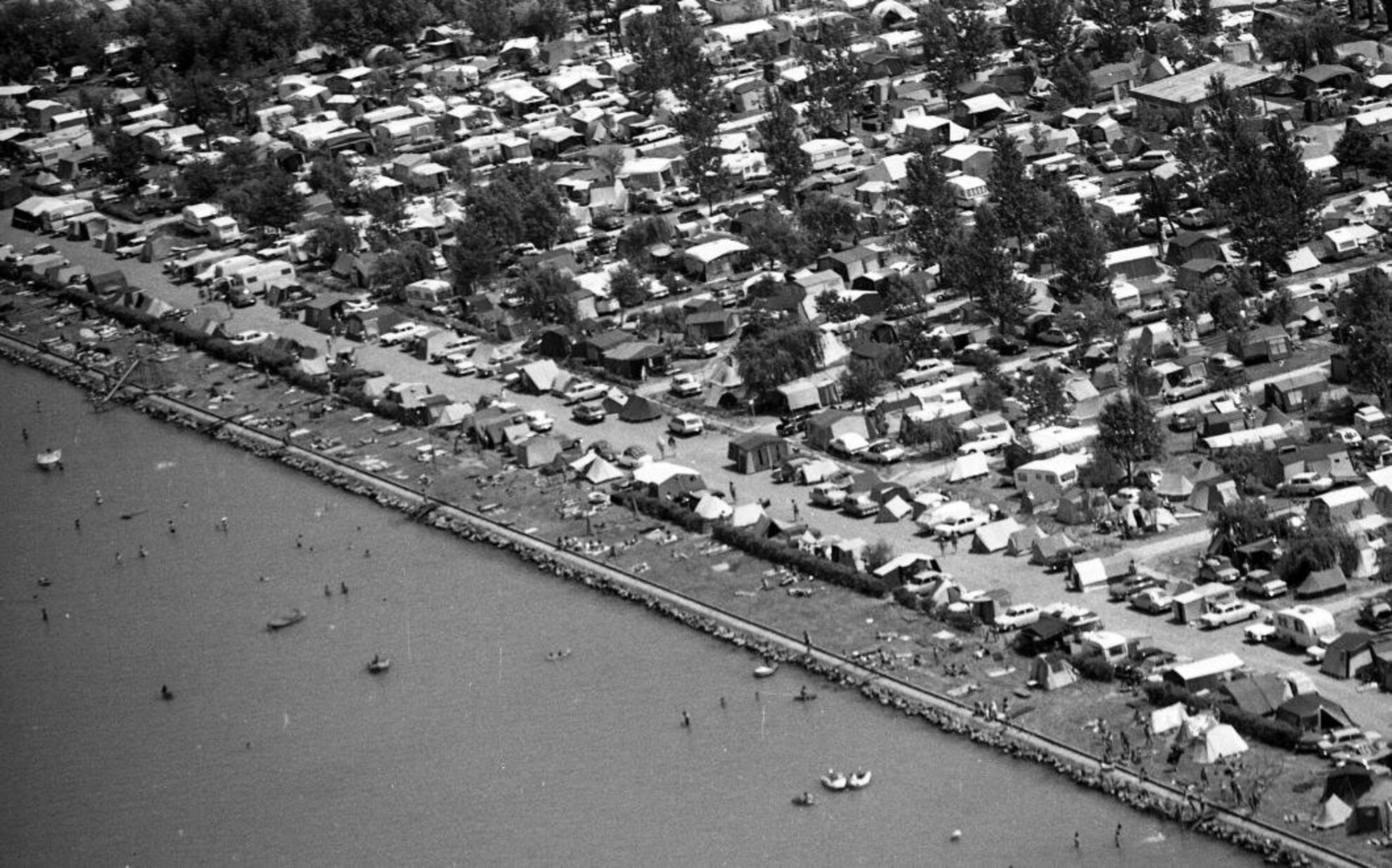

The execution of the plans was not at all in harmony with the ideas of the architects. The biggest problems were caused by the utter disregard for the prescribed building restrictions: nature and the existing properties of the area were not taken into account, and the final result was crowdedness and chaos both in terms of aesthetics and function.

The intention to reap the social benefits of Balaton superseded all rationality: the central authority wanted to give as many people the chance to spend their vacation at Balaton as possible, and to achieve this goal, they tried to erect lots of service buildings in a short amount of time. The only question remaining was how many people could the finished food stands, beach buildings and motels accommodate.

BIB stopped operating as a planning authority, and the position of chief architect, created by the Ministry of Construction, was abolished, so no one batted an eye when other materials – such as concrete – were used instead of the fieldstone proposed by Polónyi and his team. The original goal of putting up uniform buildings that are in harmony with the surrounding landscape soon fell through, and the new aim was to build enough seasonally available hotels, shops and eateries.