After the decisive Treaty of Trianon, Hungary lost most of its beach and holiday resorts, which led to the restructuring of tourism and an increase in the importance of Balaton. In addition to the middle classes and the elite, tourism became accessible to other strata of society in the second half of the ‘20s, the years of economic consolidation. As observed by renowned Hungarian author Zsigmond Móricz, traveling became an “epidemic”.

By then, it was not only the upper crust, but also much of the bourgeoisie that could afford a trip to towns in the countryside or the Hungarian Sea. This transition was the result of several factors, one of them being that more and more Hungarians had disposable free time. The concept of the “week-end” started emerging in the ‘30s: office employees and factory workers were off duty between Saturday noon and Monday morning. That’s when people began to spend their days off away from home.

In 1923 the Bethlen government started implementing the practices of the eight-hour workday and paid leave, both of which were gradually extended to various sectors of industry, as well as apprentices. However, it wasn’t until 1937 that urban workers became entitled to working a maximum of eight hours per day and 48 hours per week. Paid holidays ranged from an annual 8-18 days, depending on employment status, profession or trade and position. Between the two world wars, laborers and those belonging to the lower levels of bourgeoisie were able to take day trips, while the middle classes had enough resources to go on longer holidays.

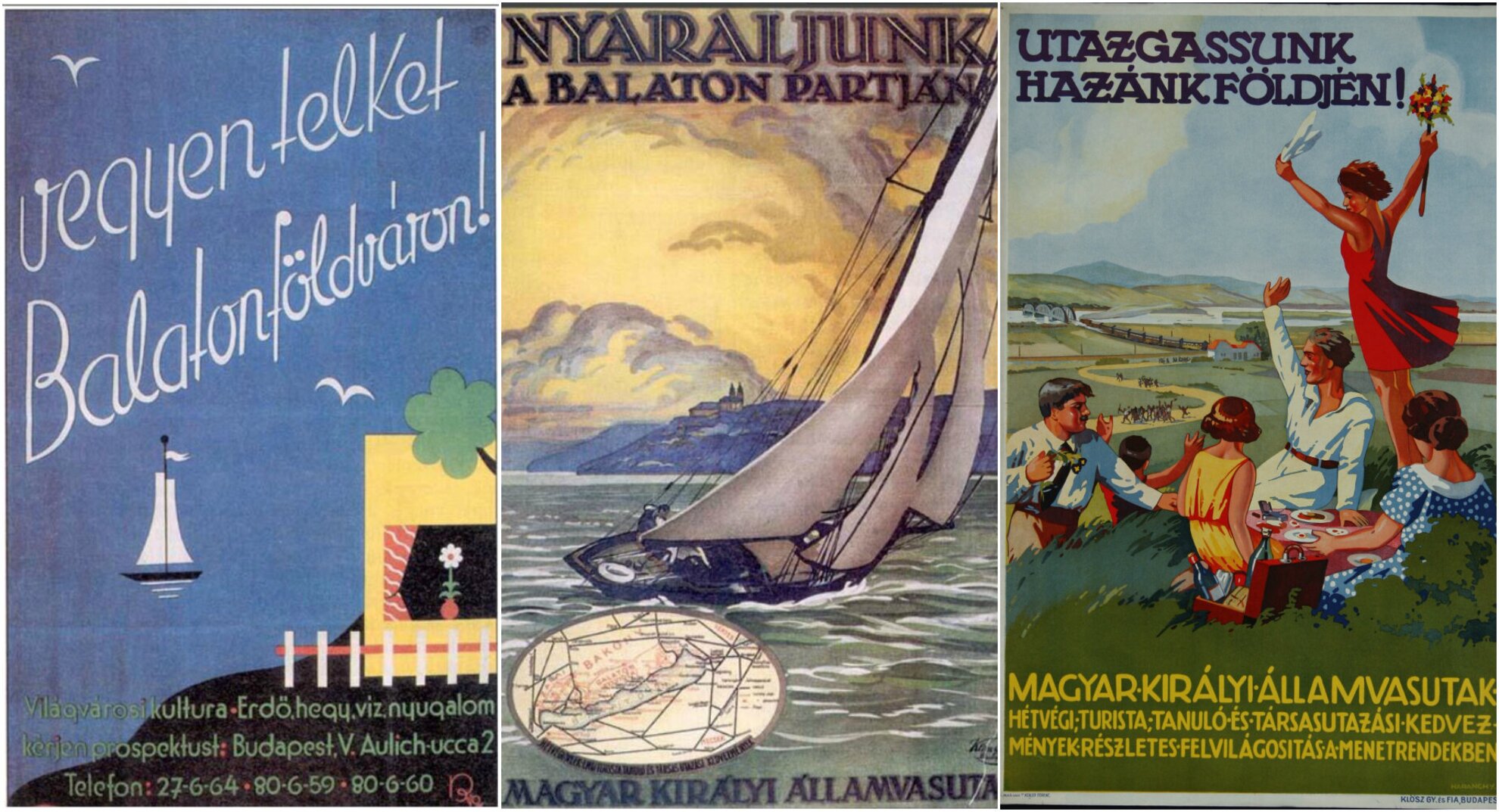

Propaganda promoting domestic tourism was strong: to convince people to spend their income at home, the government began the diversification of holiday possibilities in Hungary, providing those traveling within the country with a variety of discounts. Launched by travel agency IBUSZ and MÁV Rt., the operator of the Hungarian railway system, the most successful scheme of the era was that of the so-called “fillér trains” (fillér denoting a set of coins that used to be in circulation until the late 20th century), which over 9 years transported 1.4 million passengers to a wide range of locations in the country.

By beefing up the schedule and offering a reasonable tariff structure, MÁV sought to increase the benefits available to holidaymakers. Those traveling to Balaton were eligible to discounts ranging from 33-65%, and tourists spending more than seven days at the lake were provided with even better deals. Traveling and the Balaton region were advertised on posters with slogans like “Explore your homeland!”, and with discounted offers and a versatile event selection. The popularity of domestic tourism was also fuelled by a strong sense of patriotism (a wide-spread reaction to the Treaty of Trianon), brand new, attractive lodgings constructed throughout the country, and a new-found appreciation for sports, health and nature.

Some people wanted to enjoy the beautiful setting for more than just a few days. In the 1920s, local governments began parceling out land in lakeside communities, mainly to satisfy the growing demand from residents of the Hungarian capital. Aristocrats and artists were especially fond of the north shore. At this point, the south shore had no major townships to speak of, which made the area ideally affordable for different layers of the middle classes and intellectuals from Budapest and various towns around Balaton. A sort of construction fever broke out: countless modest looking family villas and holiday properties emerged by the lake, lots of them being named after a member of the clan (that’s where monikers like Anna Lodge and Magdi Villa originate). Going on holiday to Lake Balaton quickly became fashionable, and investors flocked to the area to cater to tourists’ needs by erecting one hotel after the other.

This was also the era when company holiday complexes were first opened. Employers from all over the country had holiday resorts built to meet the needs of workers with more moderate means. An elegant resort comprising several buildings on a spacious plot in Balatonkenese was built for public administrators working in Budapest. The holiday complex established for the junior officers of the Royal Hungarian Army was later used as the lakeside resort of the Socialist Party. Charity organizations helping trade and industry workers operated beach complexes for children.

Meanwhile, the number of private holidaymakers was rising continuously. More and more people living in cities could afford to buy their own summer residences. Those earning a monthly salary of 200 pengős (Hungary’s official currency between 1927 and 1946) – like trade and industry workers, junior officers of the armed forces, office and bank clerks, and even apartment managers – could maintain a comfortable standard of living, which also entailed going on the occasional holiday.

Plot owners hailing from bigger towns and the capital did not wish to do without the comfort they had grown accustomed to at home, so lakeside townships started establishing the infrastructure for public utilities. Some of the pensions and hotels (the ones in Balatonboglár and Balatonlelle, for example) around the lake had indoor plumbing, and several towns had gas stations and automobile repair shops as well. The number of restaurants, taverns, confectioneries and dance halls was on the rise – Balatonlelle’s Halászcsárda, Badacsony’s Hableány and Paprika csárda in Siófok opened during this era.

The waterfront areas and the town centers had a similar structure everywhere, with more up-scale pensions and hotels, the post office, shops, hair salons, restaurants, confectioneries and other service providers located side by side. These parts of town were always decorated with flowers and kept neat, clean and attractive, just like the surroundings of railway stations. Not only did these improvements make life at Balaton more comfortable, but they were also responsible for creating jobs for the local residents, who got acquainted with new demands and acquired new habits by meeting and learning from the tourists staying in their villages and towns. There was one practice the locals had a hard time adopting: they often went to the lake to fish, but they rarely swam.